OFF THE WIRE

Adam Shand

theaustralian.com.au

BARRISTER Wayne Baffsky had long suspected that consorting laws aimed at outlaw bikies in NSW would be unleashed on anybody the police did not like. The Hells Angels barrister never dreamed it would happen so soon.

The first person jailed for consorting - defined as contact with at least two people convicted of indictable crimes - was Charlie Foster, 21. He was neither a gangster nor a bikie. In fact, most people in his hometown of Inverell in northern NSW regard him as nothing more than a nuisance. Born with an intellectual disability, Foster, who reportedly cannot read or write, has never been accused or convicted of any kind of conspiracy, let alone any organised crime offences.

He was sentenced to nine months' jail in July after receiving two consorting bookings with three other men in a two-month period. Far from meeting to plan crime, Foster and his mates were going shopping when booked on one occasion.

The conviction was overturned on appeal last week after the prosecution admitted its case was weak, but that's no comfort to Baffsky, who represented Foster in the appeal. The case, he says, clearly demonstrates the potential for abuse under the new laws, which are amendments to the Crimes Act, enacted by NSW Premier Barry O'Farrell in April. If such laws spread to other states the notion of free association would be destroyed, he says.

There is no Bill of Rights underpinning the Australian constitution, so freedom of association has always been notional. A new era is dawning where police will once again have the power to tell citizens with whom they can or cannot associate, says Baffsky. NSW police are understood to have issued more than 130 first warnings to suspects, many of them bikies, and more charges are expected soon.

The draconian legislation, aimed primarily at bikie gangs, potentially criminalises contact with people convicted of indictable crime - even minor offences - whether in person, over the telephone or in cyberspace. Police do not have to prove the contact has anything to do with crime, merely that a suspect "habitually" consorts with a crook. The offence is defined as at least two contacts with at least two people who have been convicted of offences. Unlike most criminal statutes, NSW's revived consorting laws feature a reverse onus: the defendant must prove he doesn't habitually consort or he has a lawful purpose.

Two Sydney members of the Nomads outlaw motorcycle club will face NSW Local Court tomorrow charged with consorting. Lawyers such as Baffsky say the jails will soon be overflowing with men and women doing time.

Australian police have been enamoured of consorting laws since they were introduced in the 1920s. In 1928, South Australia was the first state to give police the power to prevent the mingling of habitual criminals, drunkards, thieves, prostitutes, fortune tellers and vagrants. NSW followed in 1929 (in response to a war between "razor" gangs in Sydney) then Queensland and Victoria in 1931, Tasmania (1935) and Western Australia (1955). Most of these laws were either repealed or fell out of use by the mid-80s, but summary offences legislation in some states has retained consorting provisions.

O'Farrell's new version has raised the maximum penalty from six months' jail to three years and reduced the number of bookings from seven to just two within a six-month period. In other words, you get one warning. And police are entitled to disclose the criminal record of the person with whom you are consorting.

Not only does this raise questions of privacy, it is also at odds with the notion that a person who has served their time or paid their penalty should not continue to be punished.

Former Victorian consorting squad officer Brian Murphy welcomed the return of these measures, saying they had been a highly effective "lever" to break up rings of criminals involved in safe-blowing and armed robbery in the 70s. Murphy says he would often book "cleanskins" who associated with criminals because they would "open up like ripe watermelons falling off a truck" when faced with jail for consorting. "Either they would help us with inquiries or they would be locked up for consorting. It was a great way to get villains off the street, if we chose, or just to learn who was running with who in the criminal world."

However, consorting laws have been largely ineffective in breaking up motorcycle clubs. South Australian bikies, in particular, say the laws were the making of the state's outlaw scene. In June 1974, a moral panic over bikies began after a wild beach brawl at Port Gawler, an hour north of Adelaide. It started as a disagreement between two local clubs, the Iroquois and the Undertakers, but soon affiliated clubs and friends lined up behind the two clubs. After dark, two mobs of more than 100 bikies, brandishing hockey sticks, cricket bats and motorcycle chains, gathered on the deserted beach. One was armed with a shotgun and in the melee four shots were fired. A bikie was wounded in the chest and a few others less seriously. Police made 85 arrests and, as The Advertiser newspaper later noted, South Australia had "a new breed of bad guys".

Amid public outrage, the state government directed the police to drive the bikies out of South Australia using consorting laws, and a new squad was formed for the purpose. The leader of "the Bikie Squad", Rodney Piers (Sam) Bass, was an unusual policeman by today's standards. Some bikies say if Bass hadn't been a cop he would have made a fearsome outlaw. Bass's eight-man squad were tough guys normally found in pubs and they roared around town on 750cc Suzukis and Yamahas. From 1976-1981, Bass's war on the bikers escalated and the consorting power was a potent weapon.

In 1976-77, Bass targeted the Descendants Motorcycle Club, founded by brothers Tom and Perry Mackie, after one of the Bikie Squad's motorcycles turned up at the bottom of a dam. Tom Mackie was hardly an accomplished criminal - his record comprised some minor assaults and a few fines for summary offences, including theft and forgery - but he says Bass had set out to crush him. Mackie and other club members, friends and associates racked up more than 30 consorting bookings in the space of a few months in 1977. For some members, the consorting booking was their first charge. "We could always be found in a three-mile radius between the clubhouse, a motorcycle shop, and a local pizza joint, so the police could just sit off and watch us and count off the bookings," says Mackie.

By September 1977, many of the club had been sentenced to jail terms of up to three months for consorting. Some sentences were suspended on condition the members did not continue to associate. But of course they did, whether in or out of jail. "Bass couldn't whip, flog or hang us so, having put us in jail, he could not punish us anymore," says Mackie.

It eventually dawned on police that locking up bikies was doing no good whatsoever. While in jail for consorting, the Descendants had also learnt to be real criminals. Club leaders turned the focus of recruiting from their social scene to the criminal milieu they had met in jail. Some of the members began using or dealing in hard drugs. One night early in July 1979, the climax of this conflict was reached when Bass and his squad shot dead a Descendant nominee in a sting operation at a downtown hotel. Bass and another colleague claimed they had fired in self-defence and were not prosecuted.

Three decades on, the Descendants are one of the most well-established clubs in Adelaide. The criminal element that became entrenched during the consorting era, says Mackie, had washed out of the club as members refocused on the motorcycle as the centre of club life. In the early 80s, the Bikie Squad was disbanded.

In 1981, the South Australian government held an inquiry into media allegations of police corruption arising from the Bikie Squad era, which largely cleared the force, despite lingering concerns. Meanwhile, consorting laws fell out of favour around the country amid concerns they gave police too much power. Many jurists say they have no place in a democratic society, being nothing more than "broad discretionary police powers dressed up as substantive offences", according to Alex Steel, a senior law lecturer at the University of NSW.

The revival of consorting laws followed the failure of anti-association legislation in NSW and South Australia - modelled on the Howard government's anti-terror laws - which were deemed unconstitutional in the High Court. Defence lawyers say the NSW consorting law may be a better option for police than re-drafted anti-association laws, which are still not guaranteed to pass muster at the High Court.

Broadly speaking, the anti-association laws rely on police seeking a declaration from a judge that a group is, in effect, a criminal gang. Police will then seek control orders against members preventing them from associating with other members. Baffsky says the new laws will be difficult to defend because the test is so simple. Being in the company of a person convicted of a serious indictable offence will be enough to fall foul, even if the offence was decades prior. Those charged will have to prove they have a lawful excuse to consort with such persons.

Lawyers will have to run theoretical arguments that the legislation has an implied exemption for political association. Australia's compliance with the UN's International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which mandates freedom of association, may provide some foundation for a defence, but it's far from certain, says Baffsky. Counsel may also argue that applying a reverse onus on a criminal offence clashes with the right of habeas corpus, the presumption of innocence.

However, the success of such legislation will depend on the ability of bikies to fund High Court battles. Bikies, under the banner of united motorcycle councils, raised more than $500 000 to fight the anti-association legislation in NSW and South Australia. Led by the Hells Angels in NSW and the Finks in South Australia, they won both cases and were awarded costs, but almost two years later they are yet to see a cent as arguments continue between their lawyers and the crown over what level of costs is reasonable.

They may find themselves fighting fresh legal battles before being paid for the previous victories, says Baffsky. "Justice is what you get when you run out of money," says one bikie.

Senior police in NSW believe consorting laws will provide the answer to the bikie problem, but their Victorian counterparts are taking a different approach using existing laws. Victoria Police's Taskforce Echo has been targeting criminal networks operating inside the bikie world. Contrary to popular misconception, bikie crime is mostly decentralised. Police intelligence has identified that crime tends to be carried out by cells of members within clubs, rather than being a club enterprise. Often the broader membership of the club is unaware of the nature of the crime being committed, but investigators believe the office bearers are fully aware of cells of criminality, and are often involved.

Recent arrests in Victoria have identified club members working with outsiders in the manufacture of drugs that may ultimately be sold through the clubs or to club members. Investigators are also probing the activities of individual members they suspect are involved in transnational crime with Southeast Asian groups. "Victoria has a lot of legislation that hasn't traditionally been used on the bikies. Our focus will always be serious crime and organised crime, but we're now looking at other opportunities, such as compliance with the Liquor Act," says Echo Taskforce chief, Detective Superintendent Doug Fryer.

In the past two weeks, police have raided Comanchero and Hells Angels clubhouses in Melbourne, seizing alcohol and cash. Sheriff warrants were also executed at both club houses, resulting in one office bearer from the Hells Angels being remanded in custody. The engagement and policing methods with the Victorian bikies seem to be working with crimes of violence, such as shootings, being kept to a minimum, unlike those historically seen in other states.

While Victorian police have not yet received extra powers, outlaw clubs are learning to expect a massive show of force from Taskforce Echo if they step out of line. It sends a message to club leaders, but senior officers would rather use their resources to pinch bikies for drugs or guns than for simply hanging out together. In contrast to NSW, the Victorian approach recognises that every "righteous" outlaw bikie will do time for his club. Only a few who benefit directly from criminal activity will defend a drug dealer who brings heat on the entire group.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

GIVING BACK

MOUNT SOLEDAD

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

hanging out

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

Good Friends

Hanging Out

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

NUFF SAID......

Mount Soledad

BALBOA NAVAL HOSPITAL

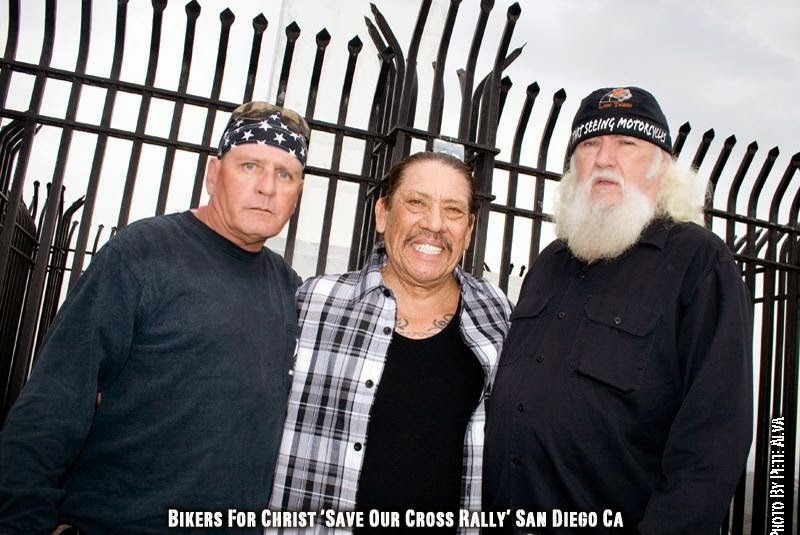

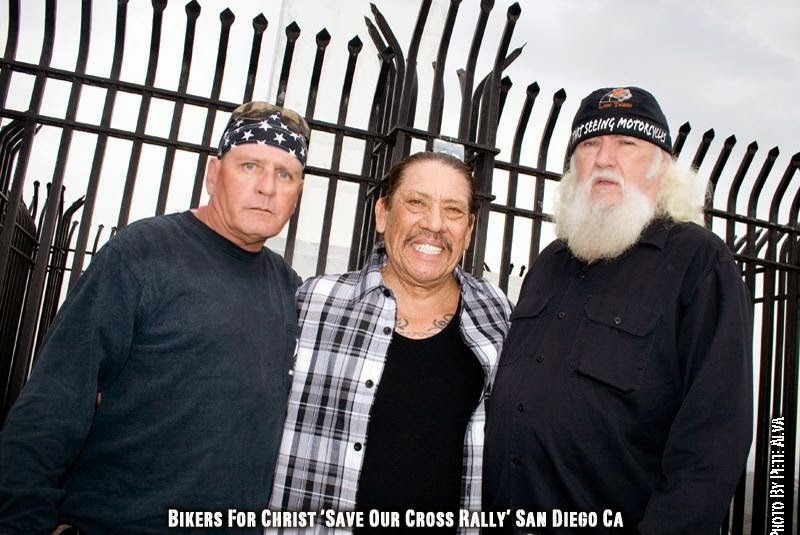

RUSTY DANNY

ANNIE KO PHILIP

PHILIP & ANNIE

OUT & ABOUT

OOHRAH...

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

American Soldier Network GIVING BACK

GIVING BACK

CATHY & BILL

PHILIP & DANNY & BILL

MOUNT SOLEDAD

bills today

EMILIO & PHILIP

WATER & POWER

WATER & POWER

bootride2013

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

ILLUSION OPEN HOUSE

FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

Friends

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com/losangeles-motorcycleaccidentattorneys/

- Scotty westcoast-tbars.com

- Ashby C. Sorensen

- americansoldiernetwork.org

- blogtalkradio.com/hermis-live

- davidlabrava.com

- emiliorivera.com/

- http://kandymankustompaint.com

- http://pipelinept.com/

- http://womenmotorcyclist.com

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com

- https://ammo.com/

- SAN DIEGO CUSTOMS

- www.biggshd.com

- www.bighousecrew.net

- www.bikersinformationguide.com

- www.boltofca.org

- www.boltusa.org

- www.espinozasleather.com

- www.illusionmotorcycles.com

- www.kennedyscollateral.com

- www.kennedyscustomcycles.com

- www.listerinsurance.com

- www.sweetwaterharley.com

Hanging out

hanging out

Good Friends

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

EMILIO & SCREWDRIVER

GOOD FRIENDS

Danny Trejo & Screwdriver

Good Friends

Navigation

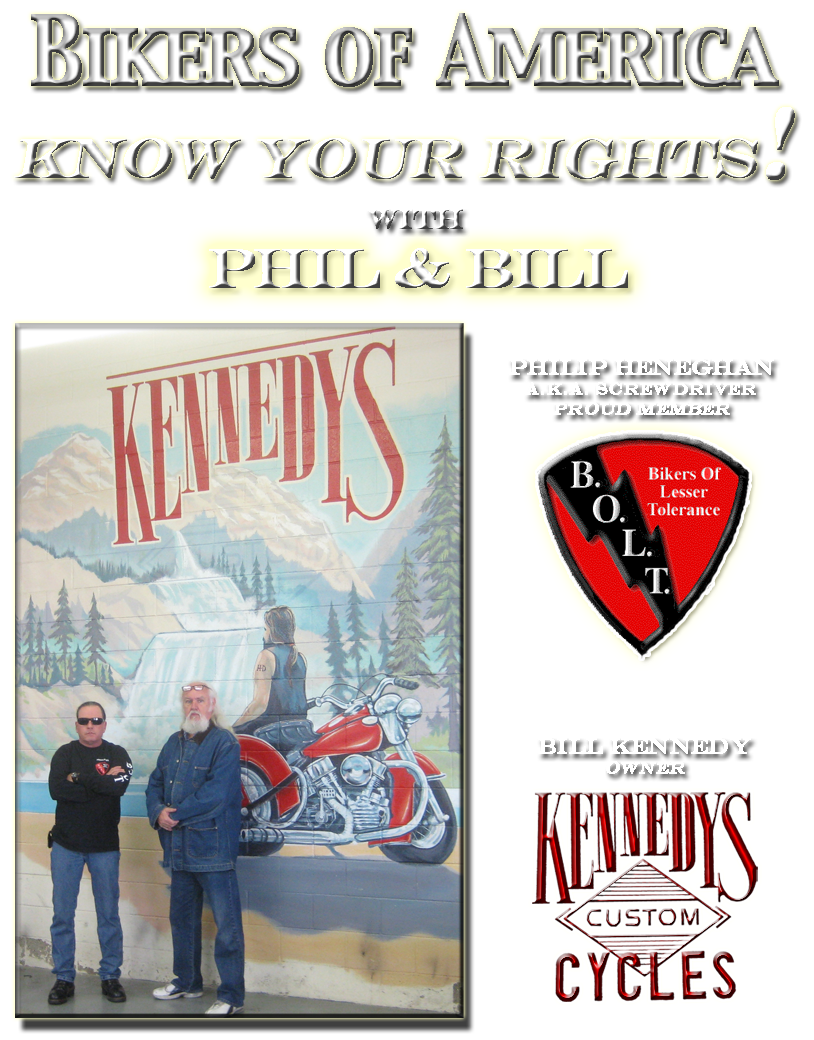

Welcome to Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!

“THE BIKERS OF AMERICA, THE PHIL and BILL SHOW”,

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

Good Times

Hanging Out

Key Words

- about (3)

- contact (1)

- TENNESSEE AND THUNDER ON THE MOUNTAIN (1)

- thinking (1)

- upcoming shows (2)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2012

(4602)

-

▼

August

(297)

- CHECK THIS OUT

- CA - LAPD to Protect and Serve? Yeah, Right.

- Scoop: Sons of Anarchy Casts Hells Angel as Nomad ...

- NH Law Enforcement Proves That Unconstitutional “S...

- California Alert: Tell Governor Brown to Veto Bad ...

- BOOT RIDE WITH S.O.A...PART 2

- Loud pipes irritate, but enhance motorcycle riders...

- AUSTRAILIA - The Governor of NSW Her Excellency Pr...

- PETITION: GIVE AFGHANISTAN HERO HIS BENEFITS BACK ...

- BOOT RIDE WITH S.O.A...

- FBI Blames Sons Of Anarchy...WTF..

- They’re Baa-Ack

- First they came for the journalists

- Babe`s of the DAY..... This is 18 and older. Rest...

- USA - MARLIN FIREARMS CLOSING ITS DOORS

- From the Owners of McMillian Mfg In Phoenix, AZ

- The New Democrat Party Symbol

- Police right to charge South Australian couple Jes...

- PIC OF THE DAY..

- [Open-your-mind] Retired Military Dogs

- CA - Stockton police working to improve MC Safety

- USA - How Long Are We Going to Wait?

- NAVY SEAL DOGS...This is just amazing.

- SOLO ANGELS PARTY

- Listen to this ad all the way through, the best pa...

- No title

- USA - Book: SEALs Angry Obama Used bin Laden Killi...

- NOW, HOW STUPID OUR YOU????? NUFF SAID

- In Search of Sponsors...........

- OCEANSIDE, CA - DOWNEY: When sound becomes noise

- Virginia - Bikers score helmet victory at Court o...

- USA - US Veterans Forcibly Sequestered in Mental H...

- CANADA - Bikers impressed by noise bylaw? Not Harley

- BROTHER IN NEED, My name is Eugene-Joesph Villacor...

- Babe`s of the DAY..... This is 18 and older. Rest...

- PIC OF THE DAY..

- Hells Angels donate food to Spearfish food pantry

- CA - REGION: CHP ups patrols for Labor Day weekend

- AUSTRAILIA - Finks launch case against legislation...

- Police allowed to track cell phones in US without ...

- CANADA - Loud pipes irritate, but enhance motorcyc...

- NUFF SAID...

- Two killed, several hurt in multi-motorcycle crash...

- USA - Hillary pushing UN Gun Ban under the radar

- Babe`s of the DAY..... This is 18 and older. Rest...

- 1ST ANNUAL DOWN AT THE YARD FUND RAISER, BE THERE

- Article about Helmet Wear...... IOWA

- CA - HEMET: Three on trial in biker club killing

- PIC OF THE MONTH....

- Go the Fuck to Sleep -read by Samuel L Jackson

- Babe`s of the DAY..... This is 18 and older. Rest...

- IF YOU WOULD LIKE TO HELP TIM KEEP THIS SITE UP CL...

- PIC OF THE DAY..

- DHS blacks out ammo purchase quantities, stockpile...

- Babe`s of the DAY..... This is 18 and older. Rest...

- PIC`S OF THE DAY..

- BREAKING NEWS UPDATE: Federal Judge Orders Kidnapp...

- USA - Legitimately Stupid

- AUSTRAILIA - Government close to finalising bikie ...

- AUSTRAILIA - Consort law sends the wrong message

- Sergeant not guilty of stealing vest

- USA - Al-Qaida linked websites threaten ex-Navy SE...

- NEW HAMPSHIRE - Different For Cop Clubs

- CORONA, CA - Officials to pull plug on red-light c...

- Fairfield CA: Crackdown on Sunday

- NUFF SAID...

- PIC OF THE DAY..

- Babe`s of the DAY..... This is 18 and older. Rest...

- CA - Enemy Of The People

- UK - Motorists reminded to 'Think Biker' as 2011 c...

- 23 Georgia bikers charged in undercover weapons in...

- AUSTRAILIA - Fit-and-proper test sees bikies lose ...

- AUSTRAILIA - Bikies lose bid for secret CMC documents

- AUSTRAILIA - Consort law sends the wrong message

- Texas Pol Sees 'Civil War'

- VICTORY: Circuit Court Orders Brandon Raub Release...

- 'Sons of Anarchy' Season 5 Promos Feature New Thre...

- Facebook court ruling: What you share on Facebook ...

- DO NOT ALLOW CHILDREN TO WATCH THIS AND DO NOT WAT...

- here's the link for the scavenger hunt at Biggs on...

- Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation

- WHAT THE FUCK...

- PIC OF THE DAY..

- Watch out, that mailbox, trashcan could be a speed...

- PIC`S OF THE DAY..

- Australia - EXCLUSIVE - Police eye bikie-tattoo ...

- AUSTRAILIA - Government close to finalising bikie ...

- USA - Here's Why The Feds Call The 'Hells Angels' ...

- AZ- Senator (Linda Lopez (D-29, AZ), Clarifies Re...

- Florida Police Officer Slams Woman into Car, Goes ...

- NEVEDA

- Babe`s of the DAY..... This is 18 and older. Rest...

- PIC OF THE DAY..

- CA: Please pass along event info to others you fee...

- CA -Your online viewing habits are private and pro...

- Facebook, ACLU: Clicking 'like' is free speech

- Unbelievable ... South Australian law

- AUSTRAILIA - Gang rivalry boils over as outlaw clu...

- AUSTRAILIA - Victoria Police bikie blitz is welcome

-

▼

August

(297)

Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!... Brought to you by Phil and Bill

Philip, a.k.a Screwdriver, is a proud member of Bikers of Lesser Tolerance, and the Left Coast Rep

of B.A.D (Bikers Against Discrimination) along with Bill is a biker rights activist and also a B.A.D Rep, as well, owner of Kennedy's Custom Cycles