OFF THE WIRE

By Gary A. Harki

wvgazette.com

The Charleston GazetteThis is the first installment in a three-part series examining the lack of police oversight in West Virginia.

Robert McComb raises his right arm as high as it will go as he sits in his house in Cedar Grove. McComb was injured during a run-in with former Cedar Grove Police Officer Johnny Walls in August. Walls is one of many officers in the state to have problems in one department and then find work elsewhere.

CEDAR GROVE, W.Va. -- When West Virginia police officers get into trouble and are fired or quit their jobs, they often jump to other departments -- the same handful of departments, a Gazette-Mail investigation shows.

The state doesn't monitor why officers switch departments, but the Division of Criminal Justice Services keeps track of their employment histories. An examination of the data -- about 14 years' worth -- shows that 166 officers have held jobs with more than four departments in West Virginia.

Officers moving from department to department after their actions are questioned - but before anything can be proven -- is a common occurrence not just in West Virginia, but across the nation, said Sam Walker, professor emeritus of criminal justice at the University of Omaha, and a police accountability expert.

"Everybody talks about the problem of gypsy cops -- officers who are employed, get in trouble, quit, then get hired somewhere else," he said. "It has been talked about but it has never been researched. Part of it is that research in policing always focuses on big cities. Small departments go off the radar screen."

There are 14 departments that have each hired at least 10 of the 166 officers that moved around the most.

Smithers, Montgomery, Shinnston, Mount Hope and Cedar Grove combined have hired those officers at least 80 times.

In the past two years, the Sunday Gazette-Mail has shown that at least 13 West Virginia officers who have left one department under a cloud of allegations have found work at another department.

"We have news stories about a particular officer when misconduct results in a very serious problem," Walker said. "We don't really have a professional system to prevent these kinds of problems."

One of those news stories in West Virginia this year focused on Robert McComb, 81, of Cedar Grove.

McComb had his knees replaced in February, but that didn't slow him down.

Last spring, he fixed up his camp near Duck, in Braxton County, putting in a retaining wall against the riverbank that had him carrying and stacking 1,800 masonry blocks.

In August, McComb had a bad run-in with Johnny Walls, a police officer on his fourth department in seven years. The then-Cedar Grove chief stopped McComb as he drove his ATV to his house.

Witnesses said Walls grabbed McComb, pulled him off the side of the ATV and slammed him to the concrete, face-first.

Walls already had a history of problems. In 2006, William Pullen won a $36,000 settlement against the town of Chesapeake for Walls' actions as a police officer there.

Now, McComb can barely walk from the camp to his car.

"I couldn't deer hunt this year," he said. "I couldn't lift the rifle."

'Last-chance agencies'

Police officers switch jobs for the same reasons anyone does -- better pay, relocation, better work environment, said Roger Goldman, professor at the Saint Louis University School of Law and an expert on police certification.

"Then you have your last-chance agencies -- every state's got them," he said.

Goldman said there are small departments all around the nation that will hire an officer with questionable conduct in his past because it's easier and cheaper.

"Typically, these agencies might have the option to hire someone else, but they usually have to get their certification and ... who pays for that?"

It costs about $1,500 for a department to send one officer to the required certification program at the West Virginia State Police Academy. With other expenses, the total cost is more than $5,000, police chiefs say. The money comes from the city, not the state.

If a city does pay for a new officer, those officers often leave for better paying jobs once certified, leaving the process to repeat itself, he said.

"It's economics," Goldman said.

Nationally, there's very little monitoring of officer movement, he said. There are 44 states that have a mechanism to decertify police, but the standards for doing so vary. About 20 set the standard at criminal convictions, he said.

"In Arizona, they can do it for ethical reasons," Goldman said.

In West Virginia, the Law Enforcement Training Subcommittee of the Governor's Committee on Crime, Delinquency and Corrections has the power to decertify officers. The committee is made up of law enforcement officers and officials from around the state. It has the power to decertify police "for conduct or a pattern of conduct unbecoming to an officer or activities that would tend to disrupt, diminish, or otherwise jeopardize public trust and fidelity in law enforcement," according to the West Virginia State Code.

In practice, though, the state only decertifies officers who have been convicted of a jailable offense, said West Virginia State Police Sgt. Curtis Tilley, who heads the LET subcommittee.

The LET subcommittee has a one-man staff and doesn't have subpoena power, which Tilley says is necessary to be able find information about what officers have done.

Departments won't give up information about internal investigations of an officer without a subpoena because they're afraid of getting sued, he said.

The past two years, legislation has been introduced that would increase the role and power of the subcommittee to allow it to decertify more officers, but both times it failed.

"We don't have the ability to investigate. We aren't charged with investigating whether something did or didn't happen, he said. "We deal with incidents where we are certain something did happen."

Wrong, but not always a crime

If anyone brings a complaint of wrongdoing by a police officer to the attention of the FBI or U.S. Attorney, they will investigate it, said Booth Goodwin, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of West Virginia.

The investigation has one purpose: to find out whether the officer committed a violation under the federal civil-rights statute, Goodwin said.

"It's an issue that deserves notoriety," Goodwin said. "It's about abuse of public trust. We take these cases incredibly seriously. ... Often, police are just doing their jobs to the best of their abilities. They walk into a situation with an individual not of the highest character. The situation lends itself to complaints."

Assistant U.S. Attorney Chuck Miller, who handles the cases for the Southern District of West Virginia has been busy. The Gazette-Mail has reported on four FBI investigations into police officers' actions this year alone.

Each case is investigated by the FBI, and its investigation is reviewed by the U.S. Attorney's Office in West Virginia, as well as by the office's civil rights branch in D.C., Miller said.

It's important to note that the U.S. Attorney's Office and the FBI are required to investigate each case, said Goodwin. They're also the only cases they can confirm are being investigating, so that the public knows allegations against law enforcement are being looked into, he said.

"We really want to make sure, if there are bad [police], we address the problem," Goodwin said. "Or the public's confidence in law enforcement diminishes."

Last year, former Dunbar Officer Raymond O. "Dale" Conley pleaded guilty to a civil-rights violation in federal court for forcing a woman to have sex with him while on duty.

Also in 2009, Matthew Leavitt pleaded guilty to two civil-rights violations for beating Twan Reynolds and illegally charging his wife, Lauren Reynolds, with driving under the influence.

The U.S. Attorney's Office is not prosecuting Johnny Walls for the incident with Robert McCombs, nor any of the West Virginia State Police involved in the 2007 beating of Charleston lawyer Roger Wolfe, Miller said.

But just because there's not enough evidence to prosecute a civil rights violation under federal law, it doesn't mean that something didn't happen, Miller said of police investigations in general.

"I don't want to say we are the last resort, but there are other remedies," said Joe Ciccarelli, FBI supervisory senior resident agent in Charleston.

The FBI is not designed to be police oversight for other agencies, he said. Those agencies need another mechanism to review allegations, he said.

"Our primary focus is not to settle disputes," he said.

Not every abuse of authority or overstepping of boundaries by police is a civil-rights violation.

"It may be wrong," he said, "but it's not a federal crime."

'Lives on the line'

After he realized the process wasn't automatic, Miller said plea agreements in civil-rights cases now include the stipulation that officers must surrender their police certification.

Leavitt's and Conley's pleas included the agreement.

In the case of Johnny Walls, Miller said there is video from his cruiser that shows McComb getting stopped by the officer. McComb didn't have his license on him and when Walls walked back to his cruiser, McComb drove off. The camera shows Walls chase him down in the cruiser, but it doesn't show how McComb ended up on the ground.

In his complaint, Walls said McComb wouldn't follow his instructions and tripped getting off the ATV. Attempts to talk to Walls for this report were unsuccessful.

According to witnesses contacted by the Gazette-Mail, Walls grabbed McComb, pulled him off the side of the ATV and slammed him to the concrete.

Miller said emergency officials said McComb was belligerent and refused treatment at the scene. The evidence before him didn't put McComb in the best light and he didn't believe he could prove Walls violated his civil rights beyond a reasonable doubt.

Robert McComb's daughter, Karen McComb, didn't expect the FBI to prosecute the case, but she wants something done about Walls and officers like him.

Karen is a licensed independent clinical social worker, a position that has put her in contact with many victims of trauma and with many police officers. She was at the scene of the Virginia Tech shooting in 2007 shortly after it happened. In 2009, she was brought in by the Charleston Police Department after Officer Jerry Jones was killed by friendly fire.

"I don't want to get down on those guys," she said of police. "It's disheartening to me, because you have people out there like this guy [Walls], and then officers that truly put their lives on the line get a bad reputation."

In Monday's Charleston Gazette: Problems with the West Virginia State Police dating back 30 years.

Reach Gary Harki at gha...@wvgazette.com

or 304-348-5163.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

GIVING BACK

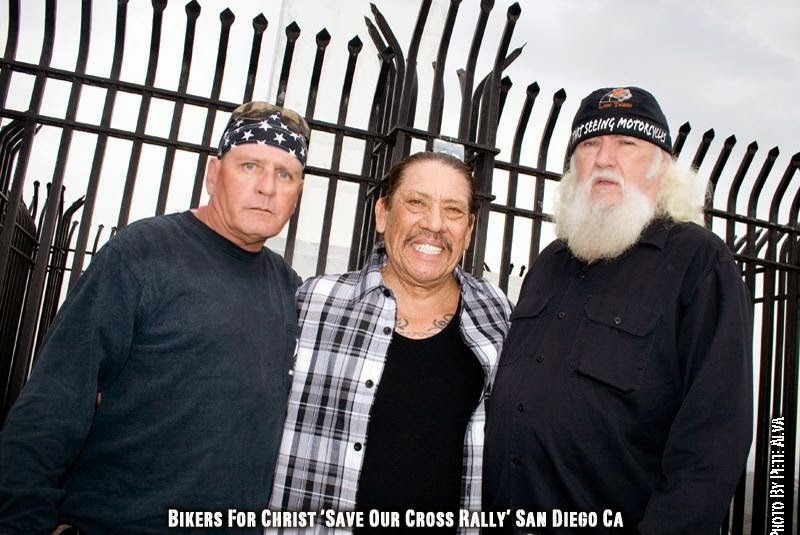

MOUNT SOLEDAD

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

hanging out

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

Good Friends

Hanging Out

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

NUFF SAID......

Mount Soledad

BALBOA NAVAL HOSPITAL

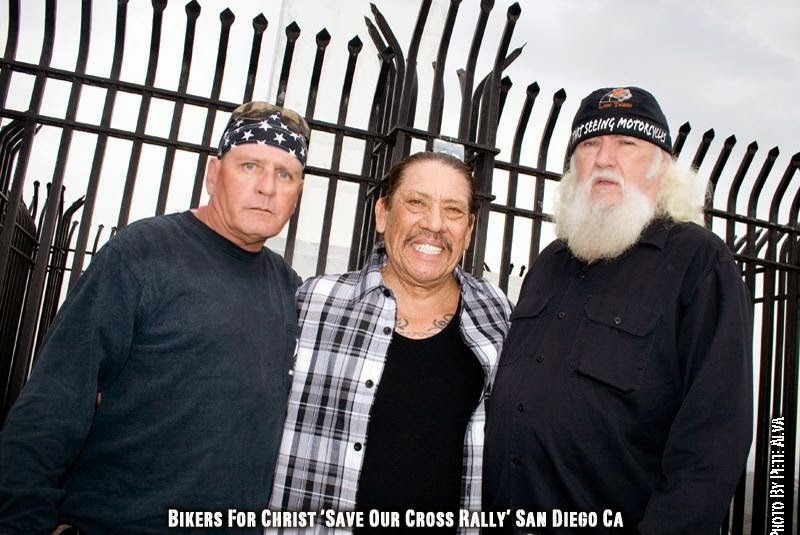

RUSTY DANNY

ANNIE KO PHILIP

PHILIP & ANNIE

OUT & ABOUT

OOHRAH...

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

American Soldier Network GIVING BACK

GIVING BACK

CATHY & BILL

PHILIP & DANNY & BILL

MOUNT SOLEDAD

bills today

EMILIO & PHILIP

WATER & POWER

WATER & POWER

bootride2013

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

ILLUSION OPEN HOUSE

FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

Friends

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com/losangeles-motorcycleaccidentattorneys/

- Scotty westcoast-tbars.com

- Ashby C. Sorensen

- americansoldiernetwork.org

- blogtalkradio.com/hermis-live

- davidlabrava.com

- emiliorivera.com/

- http://kandymankustompaint.com

- http://pipelinept.com/

- http://womenmotorcyclist.com

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com

- https://ammo.com/

- SAN DIEGO CUSTOMS

- www.biggshd.com

- www.bighousecrew.net

- www.bikersinformationguide.com

- www.boltofca.org

- www.boltusa.org

- www.espinozasleather.com

- www.illusionmotorcycles.com

- www.kennedyscollateral.com

- www.kennedyscustomcycles.com

- www.listerinsurance.com

- www.sweetwaterharley.com

Hanging out

hanging out

Good Friends

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

EMILIO & SCREWDRIVER

GOOD FRIENDS

Danny Trejo & Screwdriver

Good Friends

Navigation

Welcome to Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!

“THE BIKERS OF AMERICA, THE PHIL and BILL SHOW”,

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

Good Times

Hanging Out

Key Words

- about (3)

- contact (1)

- TENNESSEE AND THUNDER ON THE MOUNTAIN (1)

- thinking (1)

- upcoming shows (2)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2011

(5448)

-

▼

January

(444)

- Hells Angels 29th Annual Florence Prison Run

- New Zealand - Aussie Gangs And Drugs - Prohibition...

- Highway to Heil - How common is Nazi iconography a...

- Bachmann eyes cuts to veterans health benefits

- OREGON PROPOSES DUI CHECKPOINT LEGISLATION

- New Zealand - The police in Porirua say four motor...

- New Jersey - Police survey reveals motorcycle gang...

- New Zealand - Alcohol suspected in motorcycle crash

- Florida - Trial date set in biker fatalities

- Motorcycle ride to benefit Flight 93 memorial

- Prosecutors: 4 witnesses identify suspect in 1982 ...

- Proof Obama wants to continue overspending...... W...

- Sweden - Hells Angels wrap themselves in the law t...

- UK - Bikers band together to help brave Darcie

- Australia - Suspected Comancheros boss to finally ...

- Atlanta, GA - Chief Turner: 'No Decision To Disban...

- New Zealand - Whanganui debates ban on 'outlaw' g...

- Michigan - Woman in critical condition after shoot...

- U.S. - It’s still January but state governments ar...

- Cavity Search on the side of the Road?

- Ocala, FLORIDA - Motorcyclists share hope with Low...

- Profiling Bills to receive hearings by Washington ...

- Australia - Sydney bikie charged with stealing 12 ...

- Operation Home Base. Never Can Say Goodbye. 2 Proj...

- Westmoreland County, PA - 2 sides of Greensburg Sa...

- New Zealand - Turf wars expected as gang sets up..

- Australia - Bikies stopped by cops in Thomastown

- New Zealand - Kiwi police ready to fight Aussie gangs

- No title

- New Zealand - Rebels not welcome here

- "Secret account" motorcycles being returned to dealer

- Australia - Mercanti's partner breaks down while r...

- Canada - Cops? Keep Em Coming, City’s burgeoning ...

- TRAVELS, PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE...........

- REGION: Annual predawn count tracks homelessness l...

- Germany - Rocker War: large raid at the Hells Ange...

- Marine Corps Bases Japan - Ginowan hosts annual Tr...

- Bond set at $2.5M for Round Lake Beach cold case s...

- Va. Beach delegate fails in bid to ban kids on mot...

- Hells Angels Recruiting Heavily in AZ

- OCEANSIDE: Police chief's wife pleads not guilty

- That Old Time Rock and Roll

- Custom motorcycle to be unveiled in Dallas by Gene...

- Delaware - Legislators honor Patriot Guard Riders

- The future ?

- SOUTH DAKOTA: and Around the U.S.

- Court won't hold 'Don't ask, don't tell' lawsuit

- Motorcyclist found dead on roadway in Escondido

- “YO MOMA OBAMA” SUPPORTS DICTATORS AROUND THE WORL...

- Think you can ride a motorcycle?

- UTAH - FBI mistake: Salt Lake County no longer has...

- SOUTH CAROLINA: South Carolina Motorcycle Accident...

- BIKERS USA Illinois Special

- Nebraska Trying To Rip Off Bikers

- May 7th, Second Annual Biker Benefit for Second Ha...

- More from Nebraska, Trying To Rip Off Bikers..

- MMA 2011-2012 Legislative Agenda Announced

- Australia - Ulysses Bikers pizza parking exemption...

- What is going on in Europe

- Illinois

- Reprimanded or removed Judges

- TEXAS: Domestic use of aerial drones by law enforc...

- Missouri Motorcycle Helmet Law Under Attack

- WASHINGTON DC: H.R.259 -- Michael Jon Newkirk Tran...

- Australia - No apology for bikie ram raid

- Washington DC - Rehberg introduces Kids Just Want ...

- Chesterfield, VA - Chesterfield police take eviden...

- Motorcyclists gather at Capitol to lobby represent...

- Biker gang leader ‘Scarface’ sent to prison for 37...

- Australia - Police discount threat of Blacktown bi...

- Australia - Bikie figures don't lie, says Rann

- Court hears of bikie brawl 'amnesia'

- Motorcycle Safety News

- Fish Aid Music Festival - Press kit

- Canada - OTTAWA - Rallies planned to mark end of A...

- BLADEN COUNTY, NC - Five arrested for running an u...

- Australia SA Labor minister Paul Holloway attacks ...

- They Be Clubbin'

- Sentence is appealed

- LOCAL 6 "E-MAIL BLAST"

- Motorcycle flag placement

- Senate's first budget attempt spreads painful cuts...

- Nebraska Motorcycle Safety fund may get the ax!!

- Texas

- Safety coalition urges Colorado lawmakers to tough...

- "HEADS-UP VA VETS WHO CONCEAL CARRY...SERIOUS!

- Ex-Calif. sheriff surrenders to begin prison term

- Why isn't this illegal?

- U.S.: Gun raids show cartels at work in Arizona

- RISKS ON ROADS, Study: Roads are safer in urban a...

- Feds Drop Plan to Change Workplace Noise Standards

- Australia -Hells Angel faces possible jail term

- Australia - Bikie comments haunt SA police chief

- Virginia County Settles with Victim's Family for $2M

- NEW YORK LEGISLATION UPDATES: motorcycles

- facebook page "Ca businessed that discriminate aga...

- Question is.... what represents "Probable Cause"

- Motorcyclists Ask Missouri Senators to Scrap Helme...

- Australia - Bikies aren't so bad, says Commissione...

- Seattle, WA - Detective from 2008 shooting incide...

-

▼

January

(444)

Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!... Brought to you by Phil and Bill

Philip, a.k.a Screwdriver, is a proud member of Bikers of Lesser Tolerance, and the Left Coast Rep

of B.A.D (Bikers Against Discrimination) along with Bill is a biker rights activist and also a B.A.D Rep, as well, owner of Kennedy's Custom Cycles