OFF THE WIRE

BY: Travis R. Wright

Source: metrotimes.com

A daughter exhumes her father's photos of his '60s biker brethren. And you've not seen anything like it

Grown men in leather, dirty beards and fingerless gloves riding Harleys aren't always as grizzly or as grimy as they appear.

Some could be criminal lawyers, anesthesiologists or marketing gurus in boots flaunting vicarious thrills on drop-dead expensive bikes, with their trophy blondes and Bloomfield Hills houses in the rearview.

But this writer grew up around true-grit bikers, guys who wore rockers and rolled patches; guys who belonged to 1-percenter motorcycle clubs. Guys with "M/C" patches on their backs so you knew exactly who you were dealing with. These guys weren't the casual cruisers, they are, often, truck-stop bruisers.

American Motorcycle Clubs go back to the Depression era, but it was the 1947 Hollister, Calif., clash between the Boozefighters ("a drinking club with a motorcycle problem") and the local fuzz that changed American culture. The event was somewhat immortalized, inspiring Marlon Brando's 1953 film The Wild One — and anything after that involved two wheels and a cigarette. After the Boozefighters fracas, the American Motorcycle Association released a statement claiming that 99 percent of motorcyclists are law-abiding citizens, and 1 percent are outlaws. Hence the "1 percenter" tag embraced by hardcore motorcycle clubs the country over.

In the summer of 1935, a bunch of motorcyclists gathered at Matilda's Bar on old Route 66 in McCook, just outside Chicago. The men entered as unaffiliated roughnecks and left a unified gang, christening themselves the Outlaws.

In 1963, the Outlaws were the first official 1-percenter club east of the Mississippi. Expansion followed in '65, and the club established charters in Milwaukee, Detroit, Cincinnati and elsewhere. By the '70s, the Outlaws were national. Today, they roll throughout Canada and across Europe, from Italy to Serbia, with a strong presence in

Germany. Some claim they're the largest motorcycle club in the world, now that they've rooted in Japan and Australia.

Jim Miteff was a husband, father, biker, businessman and photographer from Detroit. He could build a bike from the floor up before he joined the Outlaws as a founding member of the Detroit charter in 1965. And while some in the gang tucked knives and guns into their belts and boots, Miteff rode armed with wrenches and cameras, even on stormy rides to Milwaukee. The local Outlaws dubbed him "Flash." (That's him with the camera on the preceding page.)

In those days, when the various Midwestern charters were meeting regularly under the direction of the mother chapter in Chicago, the group was without a Detroit clubhouse, so the Miteff's home in Dearborn Heights became a crash pad for Flash's extended family. He documented it all too, beautifully, from the house party comings and goings to the long highway rides, bar nights and courthouse mornings.

For what Miteff's eldest child doesn't remember, his photos filled the gaps: "We constantly had two to 20 Outlaws at our house at any given time," says Beverly Roberts, who only began to compile her father's photos a few years ago. "It was a pretty crazy house. Parties all the time. Somehow [my parents] managed to juggle it all. We were good, educated kids. The guys were rowdy, but they were always extremely nice to my sister and me. I actually couldn't have felt safer. It was one huge adventure."

Miteff's photos of those early days reveal a kind of aimless adventure and misfit anarchy, as these guys were caught between the greaser '50s and hippie late '60s. Flash was there in the very beginning, when they were wild, when they'd wear Nazi garb and touch tongues for reaction.

For Miteff, the adventure lasted from 1965 to 1969 — critical years for Detroit and for the country. He left the club in good standing. But what he documented was pure outsiderist Americana. He knew it too. "The pictures are sacred and he kept them that way," Roberts says.

So it is that Roberts, with the blessing of the club, has published in two volumes her dad's photos. Bringing them to light was an adventure in itself, one that saw her reunite with a somewhat estranged "family" and rediscover parts of herself in the process.

See, reprinting or publishing the Outlaws skull-and-pistons logo is forbidden, or so it's said. To protect club privacy and uphold his sworn oath, Flash made sure his images never went public.

Then, in 2008, Roberts compiled negatives for what would be Portraits of American Bikers: Life in the '60s. The Flash Collection. First she started selling prints at biker conventions, testing the market for the photos. Reactions were split. People loved the photos but thought she was crazy for printing and selling them.

"It's not my goal to expose anything about them that they don't want the public to have access to," Roberts says. "I can respect that because these photos were part of my private life for so long — they're like my family photo album. In publishing them, I'm also saying, 'Here's my life, my upbringing, for the world to see and judge.' That's as uncomfortable as anything." (Surely some won't know what to make of all the swastikas, switchblades, bonfires and doe-eyed women.)

Roberts was also selling her dad's prints on the same eBay store where she sold dollhouse miniatures.

People noticed, especially a few members of the Outlaws. Soon after throwing them on the Internet, she was in touch with Jingles, a club elder who handled its PR.

Jingles and much of the old Outlaws guard dug what Roberts was dishing, and these books wouldn't have been possible without his help. Unfortunately, Jingles was diagnosed with throat cancer shortly after getting approval from the club to go forth publishing with Roberts.

"A lot of people in the club thought Jingles could be spending what was the last year of his life in better ways than working on this book," Roberts says. "But I worked with him and talked with him every single day and I believe he did exactly what he wanted to the last year of his life. And he wanted to see my relationship with the club settled in a way that I could continue to work with them on these books after he passed. Both of those things happened."

The Jim "Flash" Miteff photos fantastically capture the rebellion of America's early bikers caught between eras — guys who turned a commotion into a lasting culture, two wheels at a time.

Portraits of American Bikers, Life in the 1960s: The Flash Collection and Portraits of American Bikers, Inside Looking Out: The Flash Collection II are self-published works by Beverly V. Roberts with the permission of the Outlaws. A third volume is in the works.

> Email Travis R. Wright

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

GIVING BACK

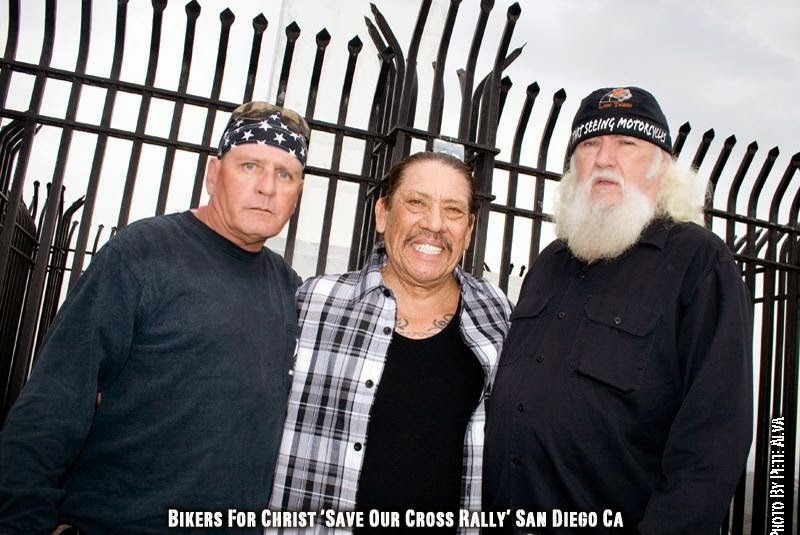

MOUNT SOLEDAD

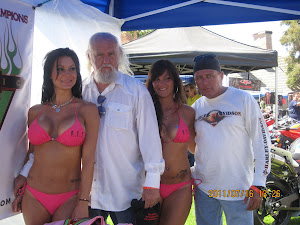

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

FRIENDS

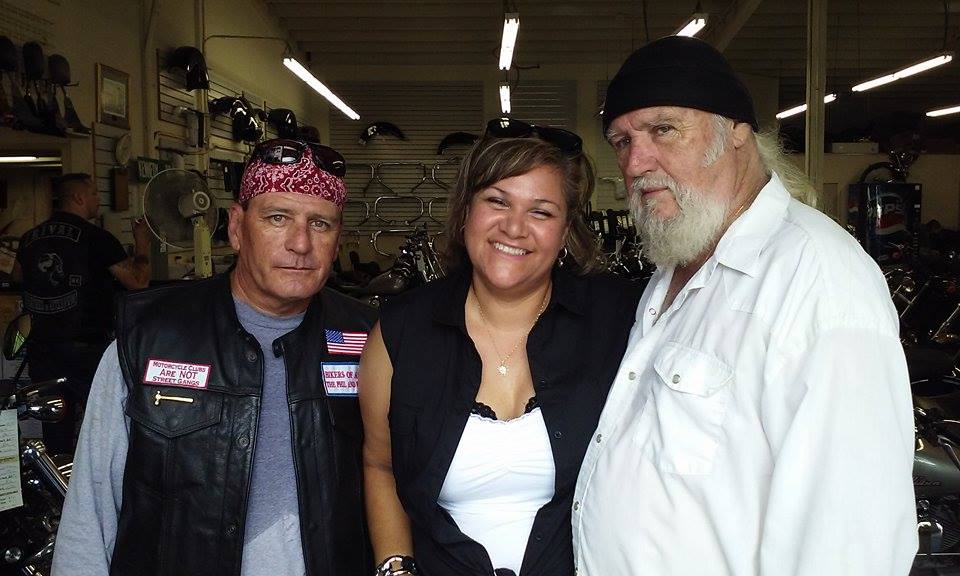

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

hanging out

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

Good Friends

Hanging Out

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

NUFF SAID......

Mount Soledad

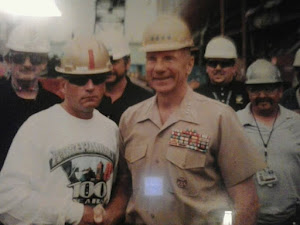

BALBOA NAVAL HOSPITAL

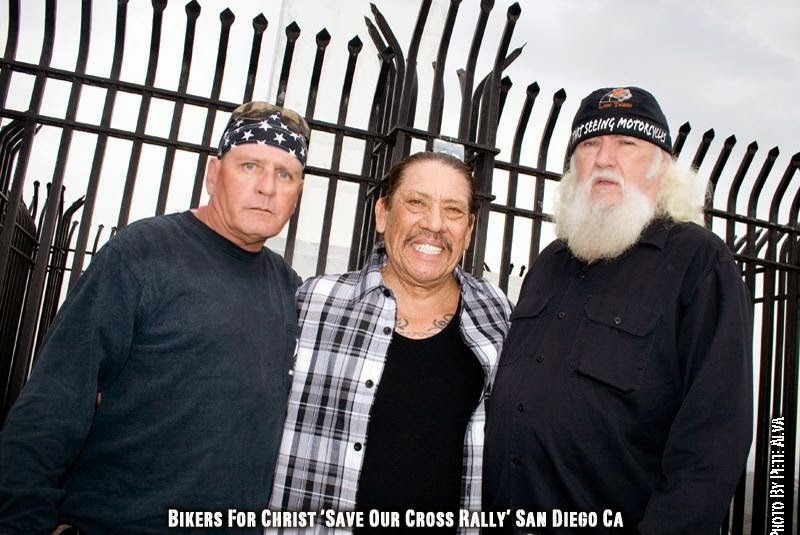

RUSTY DANNY

ANNIE KO PHILIP

PHILIP & ANNIE

OUT & ABOUT

OOHRAH...

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

American Soldier Network GIVING BACK

GIVING BACK

CATHY & BILL

PHILIP & DANNY & BILL

MOUNT SOLEDAD

bills today

EMILIO & PHILIP

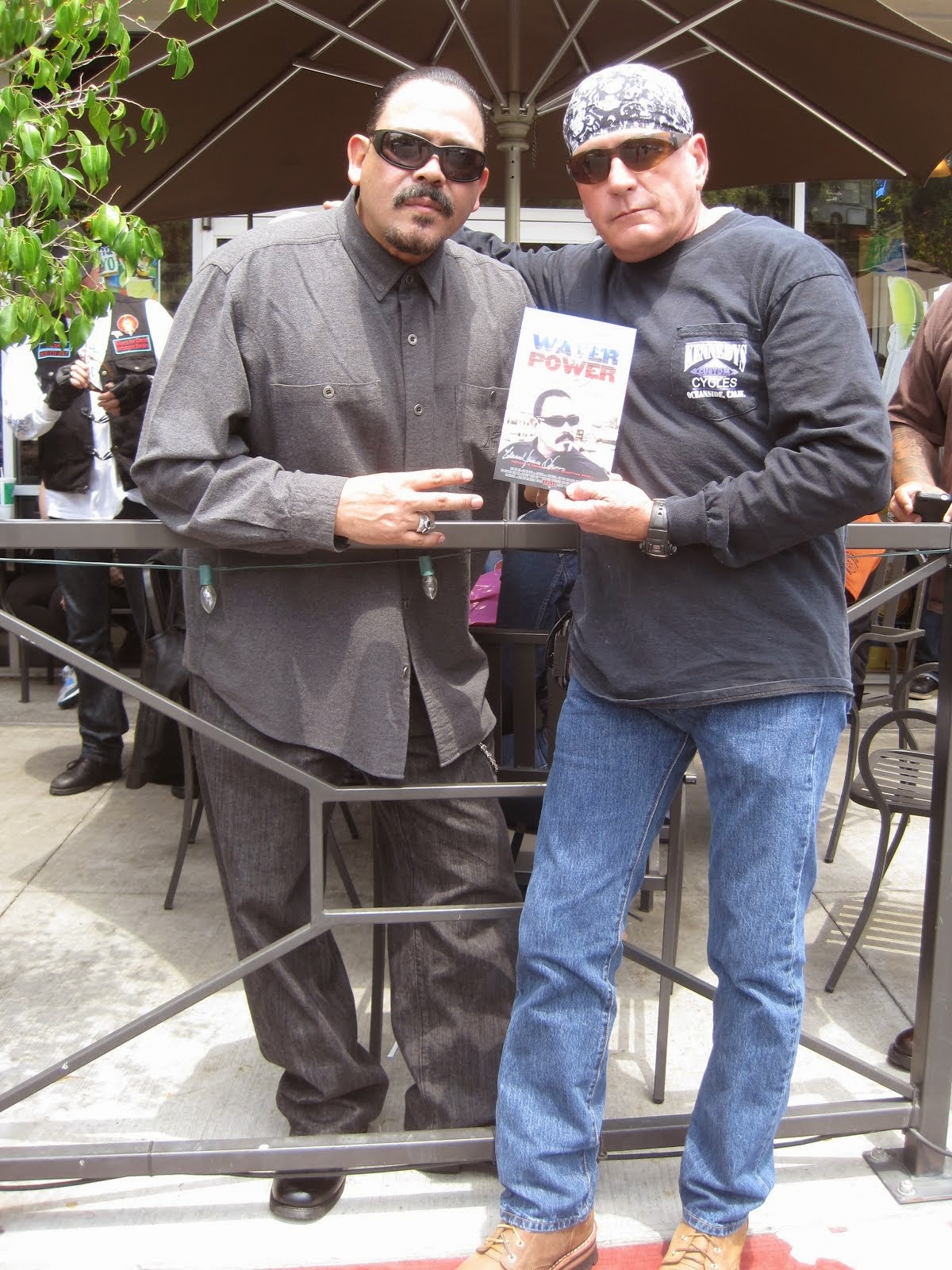

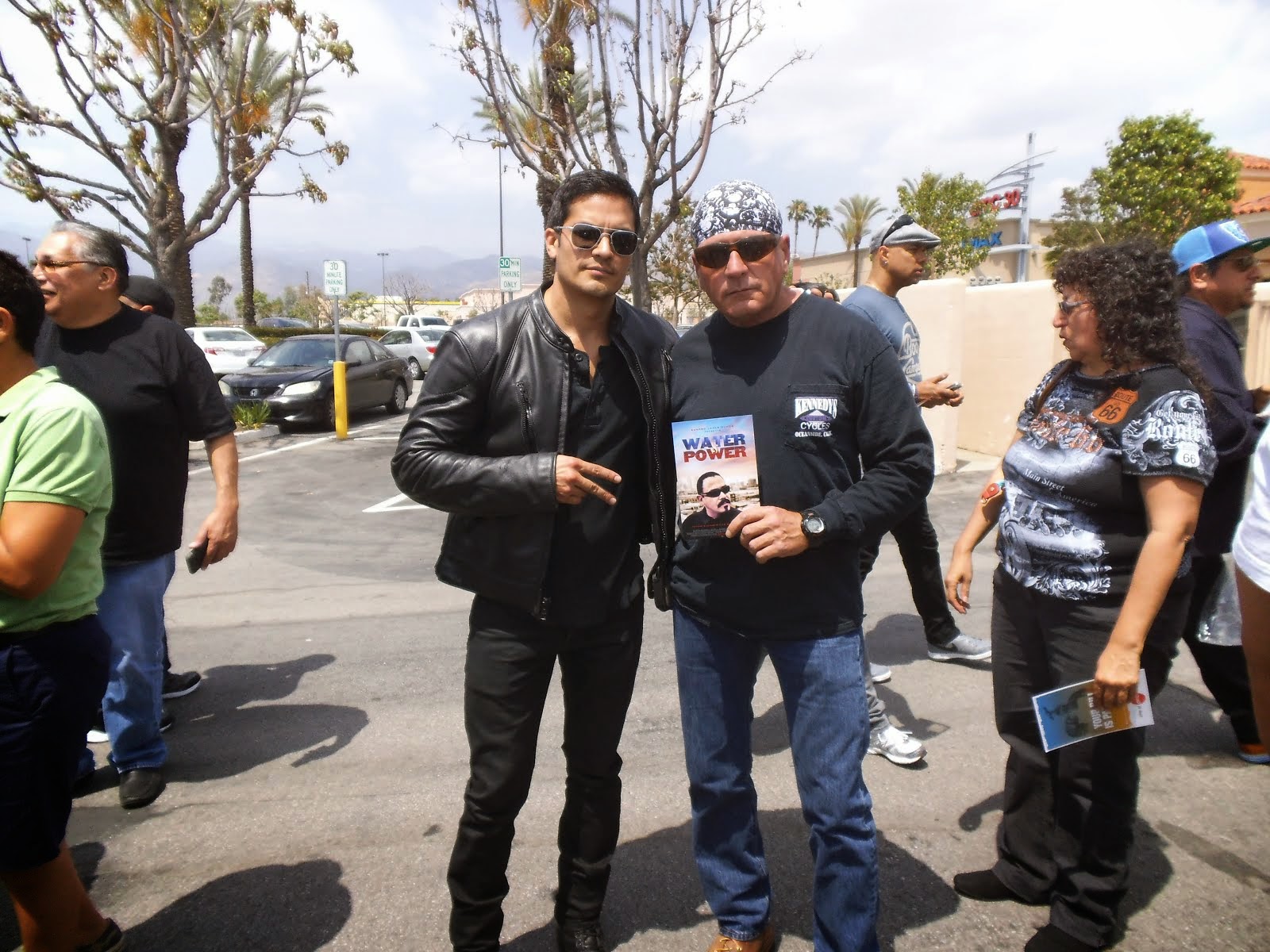

WATER & POWER

WATER & POWER

bootride2013

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

ILLUSION OPEN HOUSE

FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

Friends

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com/losangeles-motorcycleaccidentattorneys/

- Scotty westcoast-tbars.com

- Ashby C. Sorensen

- americansoldiernetwork.org

- blogtalkradio.com/hermis-live

- davidlabrava.com

- emiliorivera.com/

- http://kandymankustompaint.com

- http://pipelinept.com/

- http://womenmotorcyclist.com

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com

- https://ammo.com/

- SAN DIEGO CUSTOMS

- www.biggshd.com

- www.bighousecrew.net

- www.bikersinformationguide.com

- www.boltofca.org

- www.boltusa.org

- www.espinozasleather.com

- www.illusionmotorcycles.com

- www.kennedyscollateral.com

- www.kennedyscustomcycles.com

- www.listerinsurance.com

- www.sweetwaterharley.com

Hanging out

hanging out

Good Friends

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

EMILIO & SCREWDRIVER

GOOD FRIENDS

Danny Trejo & Screwdriver

Good Friends

Navigation

Welcome to Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!

“THE BIKERS OF AMERICA, THE PHIL and BILL SHOW”,

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

Good Times

Hanging Out

Key Words

- about (3)

- contact (1)

- TENNESSEE AND THUNDER ON THE MOUNTAIN (1)

- thinking (1)

- upcoming shows (2)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2010

(4242)

-

▼

October

(447)

- Police continue to harass citizens who record them

- Two Notorious bikie gang members arrested after ba...

- Australia, Iron bar killer jailed for 11 years

- CHARLESTON, W.Va.Two former Pagans sentenced to pr...

- Mob turncoat is sentenced in NYC to time served

- WASHINGTON DC, Motorcycle Group Supports Military ...

- AUSTRALIA, Bikie gang threat can't be ignored

- Hells Angels to sue McQueen

- Johnston City, Ill. Deputies arrest Outlaws member...

- NEW YORK:Bikers in Halloween Costumes Terrorize Up...

- Hello San Diego Volunteers

- Richmond, Va.Jury to begin deliberations in Outlaw...

- Drug accusations fly in court

- Pagans case: School bus driver who helped discard ...

- A BIKER, brawl in the heart of Bondi has left one...

- Poker run benefits Hillsborough Vietnam memorial

- Outlaws gang trial to resume Friday

- Court documents: Santa Clara cop did favors for He...

- OMCG member charged over two shootings – Petersham

- Massachusetts, Settlement gives bikers refunds

- THE top two leaders of bikie gang Notorious will r...

- Two former Pagans sentenced to probation on drug-r...

- Can ATK Cruisers Help Harley-Davidson?

- It’s A Club! Not A Gang!

- November 4th - 7th 10th Annual Rocky Point Rally.

- What is Compromise?

- Barry & Carol Sandberg Murders,PRESS RELEASE

- Oregon,Charitable Biker Event Incites 'Criminal Pr...

- The Hells Angels motorcycle gang sues Alexander Mc...

- Outlaw Country,

- Quote!!!!!!!!!!!!

- VIRGINIA:Update: Outlaws gang trial to resume Friday

- TENNESSEE:Good Samaritan chases down suspected pur...

- RICHMOND, Va. Biker gang member disputes revenge s...

- PORTLAND, Maine, Outlaws motorcycle gang member p...

- Richmond, Va, No verdict yet in Va. biker gang trial

- Tennessee, Man chases two suspects in N. Knox pur...

- ARIZONA:This Week

- Hells Angels set for rumble on the catwalk

- CALIFORNIA:2011 Iron & Lace Custom Motorcycle Pinu...

- Outlaws Motorcycle Gang Member Pleads Guilty

- Stop Complying and Start Defying

- "INCITY TIMES" PUBLISHER IN MY CROSS HAIRS!!!!

- Boston Cop Pietroski, interesting case

- Texas, Bar owners say patrons were not involved in...

- Southern California Biker Information Guide Newsle...

- MEXICO CITY,Every cop in town quits after Mexico a...

- RICHMOND, Va. Biker Gang Trial Wrapping Up In Va.

- Biker gangmember disputes revenge story

- JACKSONVILLE,FLA, Armed Forces Bike Run set

- UPDATE: Defense rests in federal trial of Outlaws ...

- Insurance companies to reimburse overcharged motor...

- Guns! Prostitution! MURDER! This New Ron Klein Spo...

- ABATE web site & Volunteer for Candidates

- AMA:Election Day is Tuesday, Nov. 2 More Info

- I ended up with a list in two commercial breaks of...

- F.Y.I. GOOD READING

- Gang member testifies he was ordered to get even w...

- Informant at Va. biker trial talks of gang 'war'

- High-ranking Comanchero charged over two strike fo...

- Pratt, Kansas, Not your average outlaw biker gang

- Virginia, Bar-B-Q arsonist must pay $25,600

- Richmond, VA, Ex-biker gang member describes alleg...

- LOS ANGELES, CA, Hells Angels v SaksHells Angels ...

- Texas, Bandidos blamed in fight outside isle bar

- Virginia - Richmond, Gang members testify against ...

- How a nerve poison became "food"

- Hells Angels Sue Saks, McQueen Design, Over Trademark

- Australia, No gun found in bikie headquarters raid

- AZ: Police will use digital cameras mounted on the...

- House Rule, H.R 4646

- AG wants to ban drink that hospitalized CWU students

- Australia, Three men bailed over Centrefold Lounge...

- Australia, Another man arrested over Zervas shooting

- Australia, High-ranking Comanchero charged over tw...

- VENTURA, CA, Hells Angel president sentenced

- Virginia, Informant speaks of 'war' with rival gang

- Former Outlaws testify as trial continues

- Canada,Police tight-lipped over reported prison sc...

- Tinley Park biker lives on through the story of hi...

- Australia, Another man charged following investiga...

- Canada, Police tight-lipped over reported prison s...

- READERS SHARE: CHECK THIS OUT

- Trial underway of Milwaukee motorcycle gang leader

- WISCONSIN, Motorcyclists to rev up for Toys for To...

- MANSFIELD, OHIO, Richland County Health Department...

- OHIO: COUNTY HEALTH DEPARTMENT RECEIVES GRANT

- CA, San Jose audit raps cop-car commuting

- October 30, 2010 "RIDE" to Stop Violence Benefit P...

- Redding, CA, Police get grant for traffic safety

- California, Traffic enforcement focus of grant to ...

- More fuel for the fire? Article in the paper

- Wall Street Journal on Obama

- F.Y.I, CA: 7 classes offered for fall at college

- New Zealand, All quiet as bikers roll into town

- Australia, Bikies not all baddies, says magistrate

- F.Y.I. Check This Out, Know how to tell the differ...

- NHTSA and Motorcycle Only Checkpoints

- Robbery Ring Disguised as Drug Raids Nets Convicti...

- Australia, Biker`s wanted over strip club fight

-

▼

October

(447)

Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!... Brought to you by Phil and Bill

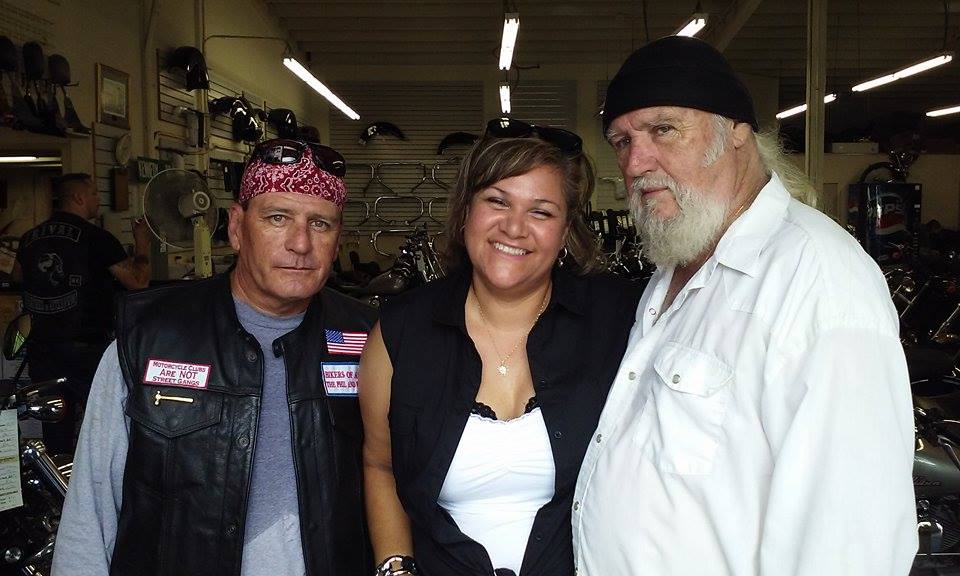

Philip, a.k.a Screwdriver, is a proud member of Bikers of Lesser Tolerance, and the Left Coast Rep

of B.A.D (Bikers Against Discrimination) along with Bill is a biker rights activist and also a B.A.D Rep, as well, owner of Kennedy's Custom Cycles