OFF THE WIRE

This article is about an SUV, however, take note, it is not a stretch to think it would be more applicable to us!

------------------

An Audible Speeding Ticket Gets Thrown Out in Ohio

Jonathan Ramsey

Correspondent AOL Autos

There are numerous tools and techniques available to police officers to issue you a speeding ticket: four different radar bands, lasers, and VASCAR for instance. The one thing they have in common is that they use a precise method to determine how fast you were going. Even if a radar gun isn't calibrated correctly, it will assess your speed based on a fixed mathematical process, and even though it's wrong it will be wrong in the same way for every car.

Police can even pull you over based on their observations and cite you for driving too fast - but they can't say they knew how fast you were going based solely on their observations.

Nor would one suspect that a speeding ticket could be supported based on an officer saying he could hear a driver exceeding the speed limit, but that's exactly what happened to Daniel Freitag.

On October 7, 2007 in the Village of West Salem, Ohio, Patrolman Ken Roth was sitting in a marked police car on the shoulder of Route 42. Roth was parked parallel with the flow of traffic, while Daniel Freitag, driving his 2006 Lincoln Navigator, was approaching him from behind. Roth would later say that he could hear the Navigator speeding, even though there was other traffic and Freitag was more than 150 yards away. Roth turned on his Genesis Radar unit and waited. When Freitag was 100-150 yards away, his headlights appeared in Roth's sideview and rearview mirrors. When Freitag passed the patrol car, Roth worked his radar unit and measured Freitag's speed at anywhere from 42 to 46 mph in the 35-mph zone.

Then he followed Freitag and issued a ticket.

Then Freitag, instead of paying the $22 fine and submitting to the 2 points that would have gone on his license, put up a defense stiff enough to impress Rocky.

Freitag and his attorney, Brent English, took the case to trial, but lost. Then they appealed the trial court's decision by noting six "assignments of error" -- mistakes made by either Roth or the State of Ohio -- that should reverse the conviction. These included more mundane assertions such as the stop being unconstitutional because the officer was out of his jurisdiction, and legally arcane protests that "the trial court erred in treating the violation as a 'per se' violation, rather than a 'prima facie' violation."

But one of the assignments of error appeared to be absurd: Officer Roth testified that he could hear the car speeding based on training he had received from an unknown member of the force several years before. Roth also testified that he could see the car speeding by watching its lights in his mirrors, even though he had no visual markers to measure the Navigator's progress.

When it was brought up that there were other cars on the road, Roth testified that he could only hear the Navigator. Going ten miles per hour over the limit. From more than 450 feet away. In traffic.

The Court of Appeals declined four of the six assignments of error, and split the decision on the other two. It threw out the Genesis Radar evidence, noting that the State didn't identify the specific Genesis model that was used. That left Officer Roth's testimony concerning his rather high-powered and bionically focused ears to be decided, and they sent the case back to the trial court to judge the issue.

The trial court, unable to factor in the radar gun evidence, decided that Roth's statements on his hearing abilities were enough, and supported the conviction.

Freitag appealed a second time, and it went back to the Court of Appeals again.

This time, appeals judge Donna J. Carr responded to Roth's assertions with phrases like "the trier of fact lost its way and committed a manifest miscarriage of justice." In her decision she wrote, "It is simply incredible, in the absence of reliable scientific, technical, or other specialized information, to believe that one could hear an unidentified vehicle 'speeding' without being able to determine the actual speed of the vehicle."

One of the Appeals Court judges disagreed with part of Carr's decision, but Freitag won the day -- two years later, mind you -- and the State won the right to pay Freitag's court costs.

We should note, though, that it has been made to sound like Roth ticketed Freitag solely based on what he heard. That's not the case. Roth ticketed Freitag based on the reading given by his Genesis Radar unit, which registered Freitag's speed as anywhere from 42-46 mph. Freitag exercised his legal rights and got that evidence thrown out. The eyebrows get raised when it takes two trips to court to assess Officer Roth's ability to hear one single car, in traffic, further away than the length of a football field, speeding.

Roth never mentioned the person who trained him to develop such hearing acumen, and if he had it might have altered the outcome by giving him the weight of an expert. We suspect -- and this is only a guess -- it could have been Homer Simpson; after all, not only can Homer smell the words written on a cake, he can hear pudding.

Now that's hearing.

Original article...

http://autos.aol.com/article/audible-speeding-tickets?ncid=AOLCOMMautogenlfpge0006

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

GIVING BACK

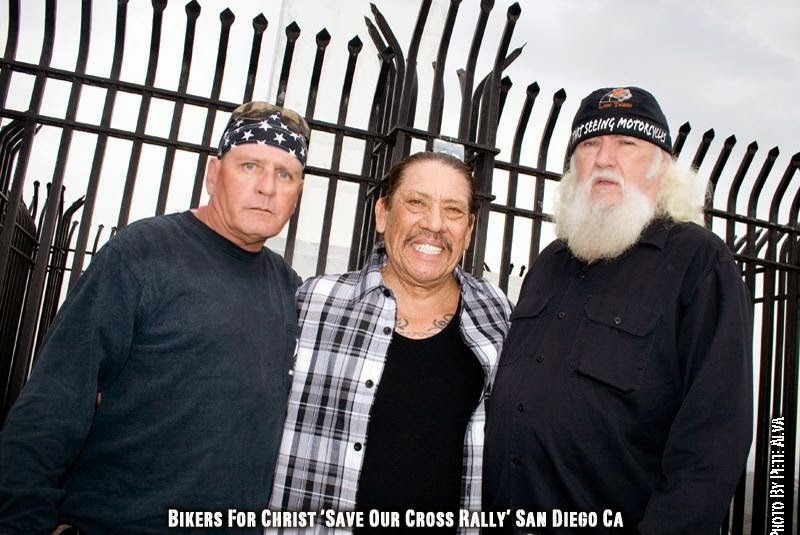

MOUNT SOLEDAD

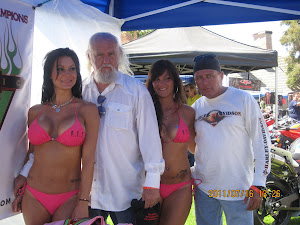

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

hanging out

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

Good Friends

Hanging Out

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

NUFF SAID......

Mount Soledad

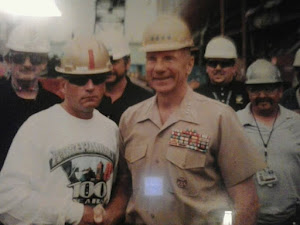

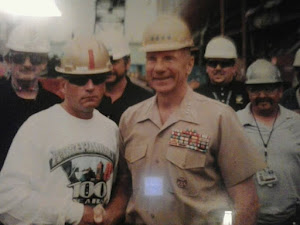

BALBOA NAVAL HOSPITAL

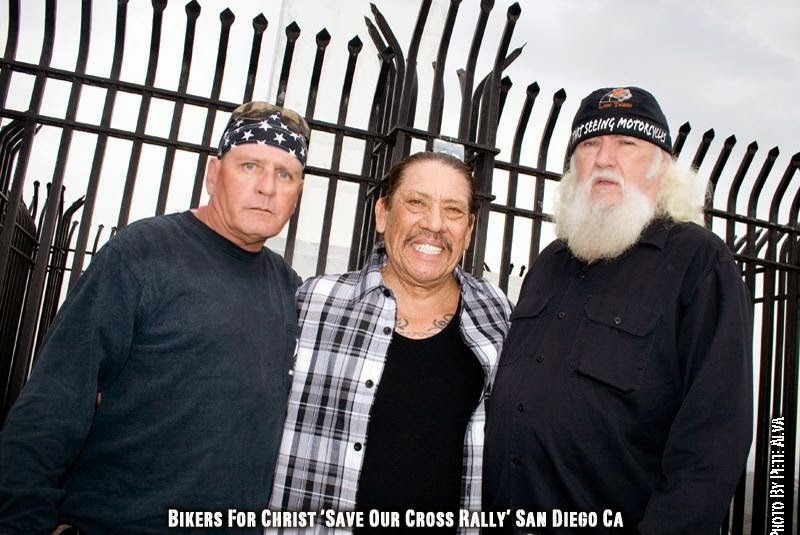

RUSTY DANNY

ANNIE KO PHILIP

PHILIP & ANNIE

OUT & ABOUT

OOHRAH...

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

American Soldier Network GIVING BACK

GIVING BACK

CATHY & BILL

PHILIP & DANNY & BILL

MOUNT SOLEDAD

bills today

EMILIO & PHILIP

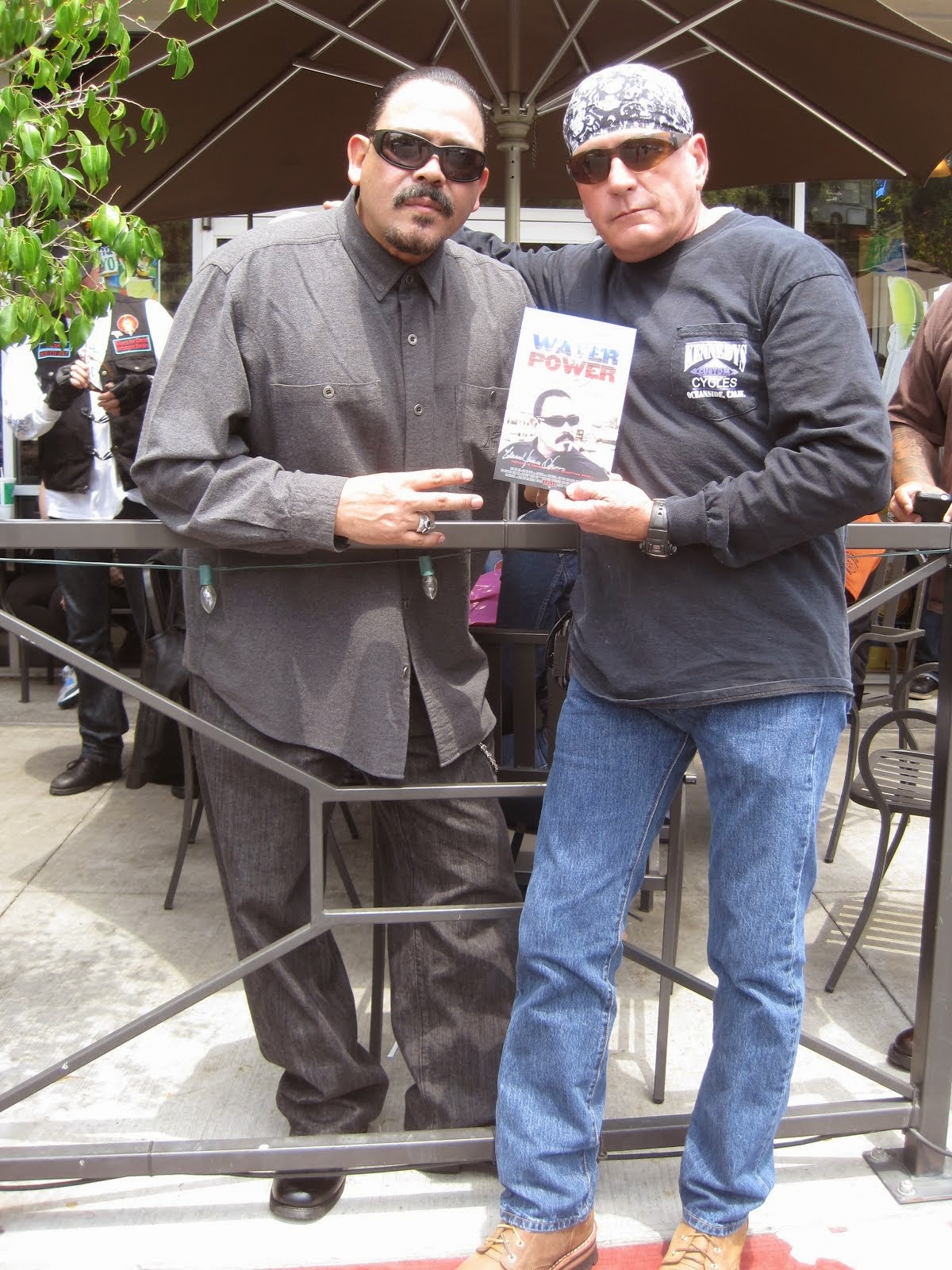

WATER & POWER

WATER & POWER

bootride2013

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

ILLUSION OPEN HOUSE

FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

Friends

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com/losangeles-motorcycleaccidentattorneys/

- Scotty westcoast-tbars.com

- Ashby C. Sorensen

- americansoldiernetwork.org

- blogtalkradio.com/hermis-live

- davidlabrava.com

- emiliorivera.com/

- http://kandymankustompaint.com

- http://pipelinept.com/

- http://womenmotorcyclist.com

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com

- https://ammo.com/

- SAN DIEGO CUSTOMS

- www.biggshd.com

- www.bighousecrew.net

- www.bikersinformationguide.com

- www.boltofca.org

- www.boltusa.org

- www.espinozasleather.com

- www.illusionmotorcycles.com

- www.kennedyscollateral.com

- www.kennedyscustomcycles.com

- www.listerinsurance.com

- www.sweetwaterharley.com

Hanging out

hanging out

Good Friends

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

EMILIO & SCREWDRIVER

GOOD FRIENDS

Danny Trejo & Screwdriver

Good Friends

Navigation

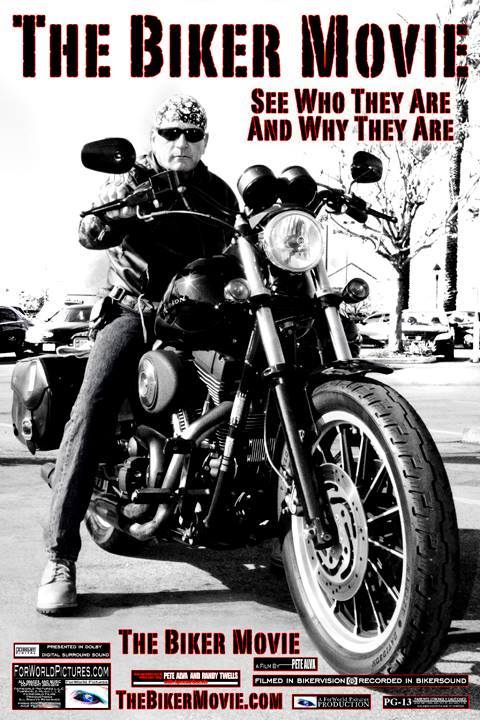

Welcome to Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!

“THE BIKERS OF AMERICA, THE PHIL and BILL SHOW”,

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

Good Times

Hanging Out

Key Words

- about (3)

- contact (1)

- TENNESSEE AND THUNDER ON THE MOUNTAIN (1)

- thinking (1)

- upcoming shows (2)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2010

(4242)

-

▼

February

(272)

- Minnesota bikers rally against careless driving

- Outlaws’ are indicted after regional ATF raids

- Seth Enslow Prepares to Jump Harley XR1200 in Las ...

- Clubs billed as brotherhoods sometimes criminal

- 16 in motorcycle club face drug, gun charges

- US magistrate frees 2 Pagan's defendants

- Executive to open biker bar/grill

- Motorcycle Gang Leader and Former Deputy Headed to...

- Home / News Kid Rock to return to Rally, Buffalo Chi

- Survival Strategies Volume I

- Pagan pleads guilty to racketeering charges

- City estimates $32k for extra law enforcement duri...

- Judge fines Clallam prosecutors for incorrectly ty...

- 12 arrested on cocaine charges in 'Operation Avala...

- 16 in motorcycle club face drug, gun charges

- Motorcycle club members nab alleged teen thieves

- Minnesota bikers rally against careless driving

- Request from Louisiana

- A Walk with Heroes veteran tribute in Daytona

- Biker sues state trooper over stop

- Harley hosts unique motorcycles, guarantees and of...

- MSU computer scientist develops tattoo-matching te...

- B.A.D. Responds To Hells Angels & Biker Discrimina...

- Cincinnati Dealer Show...Back to Basics

- Big Bear Choppers creating skeleton bike for illus...

- Five arrested in bar brawl

- House votes to renew Patriot Act

- Roads To Justice - Shadows of Govt - Part 2, by Ha...

- 2010 Daytona Bike Week Preview

- 'No Colors Allowed' Sign Causes Controversy

- Biker Birthday Love

- Just Another Random Lost Soul

- Vermont Motorcycle Noise Law Kick-Starts Loud Pipe...

- Sparked by an Outlaw’s Chopper

- Museum seeks donations of helmets

- Toronto International Spring Motorcycle Show

- Freedom Rally UPDATE !!!!

- Congress reacts with outrage to administration pla...

- MMA Members win fight for their rights and yours i...

- N.J. man pleads not guilty in beating of Pagans Mo...

- Are Loud Motorcycle Pipes Really that Big of a Pro...

- “THE BIKERS OF AMERICA,THE PHIL AND BILL SHOW”

- BIKERS attending a funeral for one of their dead m...

- Can Police Give You A Ticket For "Sounding" Too Fast?

- Looking out for everyone's rights on the road

- Nursing Home Residents Form a Biker Gang

- Renewed effort to quiet motorcycles

- Lawmakers opt for motorcycle inspection stickers

- Notable Petition Eighth Amendment and the use of f...

- Diesel Blues

- Motorcycle hall of fame announces 2010 inductees

- Shadow Govt. Pt.3 - Biker Immunity To Govt. Disease

- quotable quote

- Dirico Motorcycles and Aerosmith Hit the Lottery

- Could the Hells Angels be considered a franchise u...

- CALL TO ACTION: BIKERS WHO WOULD TRAVEL TO TENNESSEE

- Sask. will rewrite gang colours law

- Shadow Govt. Pt.3 - Biker Immunity To Govt. Disease

- When B.A.D. is Good

- New Zealand "Gang Colors" Laws... Stay InformedI

- Thunder in the Rockies could be on the move

- Murder supsect caught...after police shut down the...

- News from Washington

- Sun Showers

- Joining Outlaws Motorcycle Club earned deputy his job

- The one story I really want to discuss with you al...

- Former AMA Board Chairman Dal Smilie sentenced

- Gang affiliation addressed in torture case

- How Important Is Prospecting !!!

- Community Gathers To Say Goodbyes To Three Recruits

- Motorcycle hall of fame announces 2010 inductees

- MAINE LEGISLATURE TAKES UP MOTORCYCLE NOISE ISSUE ...

- KY Call to Action: Say NO to "criminal gang" bills

- Anti-association laws defended

- Plan for updating noise ordinance advances

- State of Discrimination - Part One

- Harley dealer will add Triumph

- Public Notice

- Smokin'Sin Taxes - Part 1

- More training for new motorcyclists?

- DUI and Motorcycles

- Florida Biker Pulled Over for Wearing Gladiator He...

- Does the Fourth Amendment cover 'the cloud'?

- Calif..: Traffic Tickets Fines (01/06/2010) - Good...

- Cops keep eyes on outlaw gangs

- MSO Motorcycle Safety Org.

- Traincops.com Presents Outlaw Motorcycle Gang Inve...

- Should attorney’s fees be awarded to attorneys or ...

- 2010 Bike Week Events

- Allstate Announces Dave Perewitz Custom Pro Street...

- Why Don't...

- A Sad and Tragic Day

- Oregon Motorcycle Riders Converge on Capitol

- The Word "Mandatory." Can it Ever be Used by the A...

- PhD in Engineering on FMVSS standards

- Motorcyclists ask for fair treatment

- Rep. seeks to quiet motorcycle noise, mandate helmets

- FairTax Presents Second Freedom Ride - FOR IMMEDIA...

- Utah Bill to Ban the Use of Aftermarket Exhaust Sy...

- Govt. Gangs Envy Motorcycle Clubs

-

▼

February

(272)

Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!... Brought to you by Phil and Bill

Philip, a.k.a Screwdriver, is a proud member of Bikers of Lesser Tolerance, and the Left Coast Rep

of B.A.D (Bikers Against Discrimination) along with Bill is a biker rights activist and also a B.A.D Rep, as well, owner of Kennedy's Custom Cycles